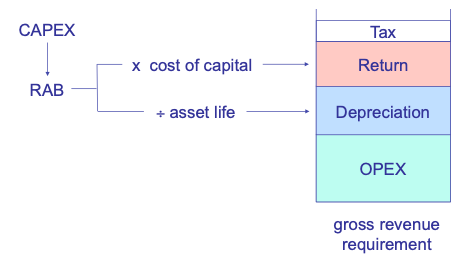

It ought to be straightforward to explain to people how regulated revenues are calculated within the UK’s framework of economic regulation. In simple terms, customers:

cover an efficient firm’s operating costs pound-for-pound as costs are incurred;

pay for investments via annual instalments over the life of the built assets; and

provide a return to investors in exchange for the financing that investors provide to bridge the gap between money going out to contractors/suppliers/etc. and payment coming in from bills.

i.e.:

revenue = opex + depreciation + allowed return + tax

Except that’s not quite what we see when we pick up some of the UK regulators’ price control decisions. Ofgem, for example, will tell you that:

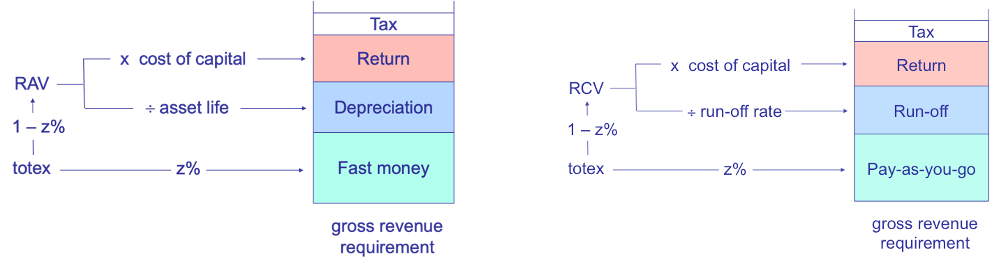

revenue = fast money + depreciation + allowed return + tax

The building blocks in Ofwat’s calculated revenue entitlements are:

revenue = PAYG + RCV run-off + allowed return + tax

Similarly, when someone asks what a regulatory asset base (RAB) / regulatory asset value (RAV) / regulatory capital value (RCV) is, the simple answer is: a RAB is a measure of the capital expenditure that regulated companies have incurred on customers’ behalf but customers have not yet paid for. Except that Ofwat’s and Ofgem’s RABs, strictly speaking, nowadays contain unpaid operating costs as well as unpaid capital costs.

How did this different structuring come about?

We need to wind the clock back to 2008-12. One of the big talking points in regulation at this time was ‘capex bias’.* Specifically, the perception was that, when faced with a choice of expenditures, regulated companies were too frequently opting for capital solutions over operating solutions, even when the latter offered a lower whole-life cost.

There were probably three main reasons why this was the case.

First, opex and capex allowances were being set in different ways. Typically an opex allowance would be calibrated via some sort of top-down benchmarking of the efficient level of total annual operating expenditure, while a capex allowance would be built from a more bottom-up, more granular assessment of investment needs and costs. The different approaches meant that a company might be able to ‘escape’ from its regulator’s benchmarking, and obtain a higher amount of funding, by moving spend from opex to new capital projects.

Second, regulators might historically have had two separate and different efficiency incentive schemes: one for opex and one for capex. The opex incentive scheme would typically be higher-powered than the capex incentive scheme,** such that a company would in many cases make money by minimising operating costs (and banking the opex incentive scheme payouts) and incurring capex (taking the capex incentive scheme hit).

Third, as set out above, opex would be matched by revenues pound-for-pound but capex would be paid off in instalments over a period of many years. Once in the RAB, that capex would earn a return. The level of that return could, in turn, influence spending decisions. If, for example, the return looked low, a company might try to avoid adding any more costs into the RAB. If, however, as was more often the case, the return looked quite enticing, the firm might actively seek out ways of growing the RAB and getting more of that return - i.e. by opting for capex solutions over opex solutions.

The conventional building block framework

After a period of debate and discussion around this topic, Ofgem and then Ofwat concluded that they were unwittingly creating perverse incentives and that the way to dampen the capex bias was to eliminate the compartmentalisation of opex and capex within their regulatory frameworks.

You can find some of the original papers that Ofgem and Ofwat published outlining their thinking here, here and here. But, in a nutshell, from around 2013-15, we were all to talk and think only about energy networks’ and water companies’ total expenditure (totex).

This required three main changes in regulatory methodology.

Totex benchmarking - rather than scrutinise opex with one pair of eyes and then look at capex through a different lens, future cost assessment would be built wherever feasible from totex cost models - i.e. benchmarking that compared companies’ total amount of actual or planned expenditure.

Totex incentives - the separate opex and capex incentive schemes would go in the bin, and in their place Ofgem and Ofwat would have a single totex sharing rule, in which companies would take x pence in the pound of any under- and over-spending regardless of the type of expenditure.

Totex cost recovery - the twin tracks for opex and capex shown in the diagram above were to be replaced by a structure in which a fixed proportion of totex would be paid for by customers pound-for-pound in the year cost was incurred, with the balance of the expenditure going into the RAB.

Note that the last of these innovations required Ofgem and Ofwat to find different labels for their price control building blocks. The green building block in my diagram was now to be called ‘fast money’ or ‘pay-as-you-go’ (PAYG). Ofwat also decided that it would be helpful to replace the term depreciation with the more all-embracing label ‘RCV run-off’.

Ofgem’s (left) and Ofwat’s (right) building block framework

It is probably worth recording at this point that not all regulators bought into this big revamp of the regulatory framework. The likes of the CAA and the NI Utility Regulator looked at what Ofgem and Ofwat had done and concluded that they would stick with the more traditional approach shown above.

Were they right to be skeptical? Or was totex regulation a significant step forward in regulatory methods?

I’ve definitely encountered situations, particularly ~10 years ago, in which the switch to totex regulation made the affected companies less reluctant to take on new operating costs. But there have always been wrinkles, which I think have grown over time, and which have made it impossible for companies to be blind to the opex/capex classification.

In particular:

The regulators from the beginning found it challenging to put all expenditures into totex benchmarking models. Ofwat, for example, moved in PR19 and PR24 to benchmark only ‘botex’ (base operating and capital maintenance expenditure), and even then the suggestion that a regulator can assess the efficient level of non-opex costs in a top-down way, without looking at the bottom-up drivers of future region-specific challenges, has proved controversial;

The claim that the regulators had been able to equalise efficiency incentives never really rang true, particularly in situations where a company has to compare recurring annual opex vs a one-off capital spend;

When deciding how much totex should be funded via PAYG or fast money and how much should be funded via the RAB, the regulators from the outset have been guided by the ‘natural’, underlying opex-capex split. Which meant that the opex-capex distinction never really went away.

This all culminated in a recommendation from Sir Jon Cunliffe this week that the water industry regulator should move on from totex:***

This would mean that separate allowances are provided for base capital expenditure (such as replacing a pipe or pump), base operational expenditure (such as energy or labour costs) and enhancement expenditure (investments that improve services, such as upgrading a treatment plant or investing in a new reservoir, or on a smaller scale, replacing pipes with higher grade materials)

(NB: Since this is the third time in three posts that I have mentioned Sir Jon’s views, I should probably be clear: the report published on Monday is a mix of recommendations to government and advice to the water industry’s future regulator(s). Our independent economic regulators are not obligated to accept Sir Jon’s critique.)

Personally, I would/will be quite happy to see totex go. It will undoubtedly make economic regulation easier for outsiders to understand (and make it easier for me to write my Guide to Economic Regulation!).

But, at the same time, as I hope this post reminds us, there were good reasons for Ofgem and Ofwat to want to try something a bit different. If we are going back to a world where talking in terms of opex and capex isn’t taboo, regulators will have to remain vigilant to the risk that compartmentalisation might unwittingly load extra cost into the system.

Notes:

* It seems a bit strange to be talking about capex bias in a week when Ofwat has been criticised for tolerating under-investment.

** Opex incentives typically allow companies to retain any savings they can make in full for a period of several of years, whereas capex incentives normally provide for some sort of sharing of under-spends between shareholders and customers.

*** Sir Jon’s recommendation was driven primarily by his sense that totex regulation has meant that capital maintenance has been neglected. His report states that the reintroduction of separate allowances “will result in reduced flexibility for companies. However, in the Commission’s view, the flexibility introduced by the totex approach, from Price Review 2014, has come at the cost of capital maintenance. Given the pressures on the existing infrastructure, the consequences of infrastructure failures for customers and the environment, and the lower tolerance for failure, the Commission believes a move back to a model that gives greater assurance that the existing infrastructure will be maintained and renewed is necessary.”

I do think a further unfortunate consequence of Ofwat’s move to totex regulation was it allowed the water specific adherence to infrastructure renewals accounting to disappear (and this underlies part of the Cunliffe concern in my view). I wouldn’t say IRA was perfect by any means but it offered some transparency about what companies needed to spend and were charging for underground capital maintenance and whether unfunded future liabilities were being built up. This is all lost with PAYG and RCV run off rates which the regulator has ended up massaging to meet other objectives.