Inflation indexation

One of the foundations of the UK’s model of regulation is that regulated companies’ various entitlements index with inflation. Except, starting next year, that won’t be quite true any more for Britain’s energy networks…

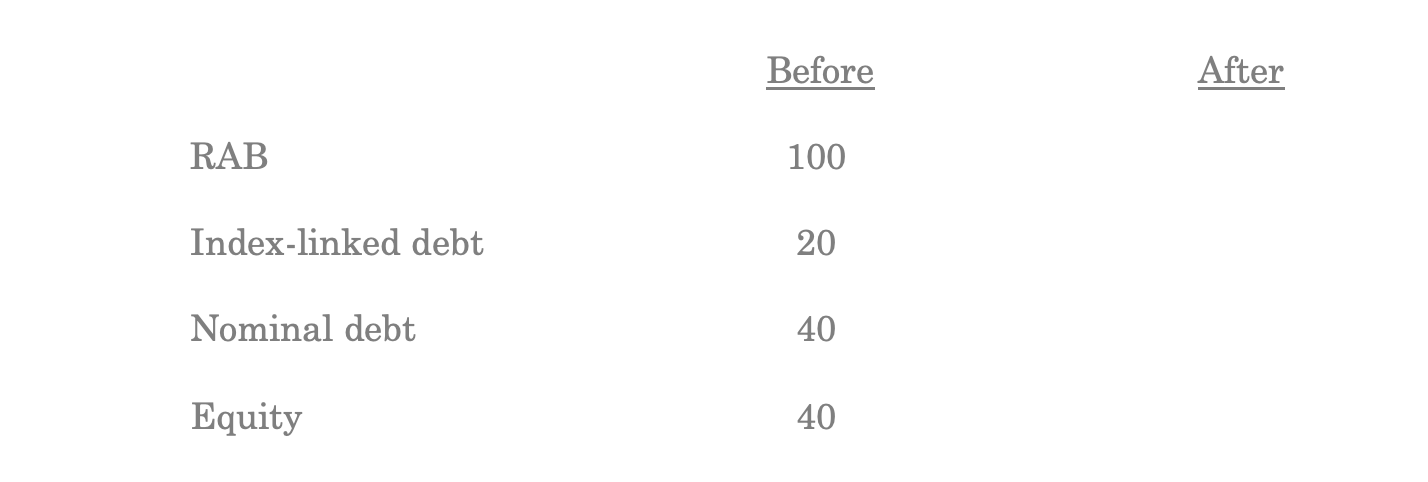

To understand how and why Ofgem is shaking things up in its RIIO-3 review, we need to look back at one of the effects that inflation indexation has had during the UK’s recent economy-wide inflation shock. In the table below, I describe a typical regulated utility company. The firm has a regulatory asset base (RAB) worth £100. It finances itself 60:40 with debt and equity. One third of its borrowing is in the form of index-linked debt and two thirds of the borrowing is in the form of conventional nominal debt.

The sudden spike that we have seen in inflation since 2021 has probably added around 15% to consumer prices* over and above the increases that we would have seen had inflation run at a normal rate (e.g. if the Bank of England had met the government’s 2% inflation target). How has this impacted our regulated firm’s RAB and our regulated firm’s financing?

First, because regulators provide for RABs to index in line with out-turn inflation, the regulated firm’s RAB is 15% higher now than anyone could have foreseen five years ago.

The principal on index-linked debt has also indexed in line with inflation, meaning that the amount owed to lenders has also increased by the same 15%. But the principal on conventional nominal debt is fixed. High inflation therefore has had no effect on the majority of the firm’s borrowing.

The value of the regulated firm’s equity can be calculated as the difference between the value of the RAB and the total sum of the firm’s borrowing - i.e. in this case,

£115 - £63 = £52.

Focus on the last line of the table. It’s worth dwelling here for a moment because we can see that our 15% inflation shock has resulted in an eye-catching 30% increase in the value of the firm’s equity - a pretty handy return for shareholders, by any objective standard.

For the avoidance of doubt, this isn’t a quirk of the specific numbers I’ve chosen. What we are seeing here is an innate quality of the UK’s regulatory model: the typical regulated firm is “leveraged” to inflation, in that any 1 percentage point change in the rate of inflation - up or down - will change the firm’s equity valuation by around 2 percentage points.

It’s fair to say that this leverage never really attracted much attention prior to 2021 because inflation typically ran very close to 2% in most years and because the value gained or lost by regulated companies each year due to perturbations in inflation was relatively small. Then all of a sudden inflation spiked in a way that no one really anticipated and regulated utilities suddenly generated significant financial out-performance** almost out of nowhere. (Citizens Advice have been more acerbic, characterising this feature of the UK regulatory system as a “loophole” that has resulted in “windfall” profits “dropping into companies’ laps”.)

Ofgem recognised as far back as 2022 that this inflation leverage was an issue that it couldn’t just walk past. After consulting during 2023 and 2024, it came to a set of proposals last year, to be implemented starting April 2026, that will fundamentally alter the structure of regulated energy networks’ cashflows.

First, Ofgem is proposing that the portion*** of companies’ RABs that is financed by conventional nominal debt will no longer index in line with inflation. This is intended to remove the potential for windfall gains and losses if inflation at some point in the future again moves off its normal track.

(The best way of seeing this is to imagine what would have happened if the new rules had been in place five years ago. The RAB for our stylised regulated firm would only have indexed by 60% x 15% = 9%. This, in turn, would have transformed the over-sized equity return in the previous illustrations into a simple 15% inflation-linked increase in value.)

Second, as a direct consequence of part-removing RAB indexation, Ofgem will in future have to provide for the return that is due on the non-indexing part of the RAB to be paid annually in full nominal terms rather than in an index-linked form. (See section 6 of Part 4 of my Guide to Economic Regulation if it is not immediately clear what difference this makes.) To use Ofgem’s language, the allowed return from next year onwards will be a “semi-nominal return” - i.e. a part nominal / part-index-linked cash return.

These are big shifts. Up until now, if I were asked to characterise the key features of the UK regulatory model, I would have highlighted, among other things, that UK regulated companies have RABs that index in line with out-turn inflation and deliver an index-linked rate of return. That soon won’t be true any more.

We wait to see whether other the regulators will follow Ofgem’s lead in upcoming reviews in the UK’s other regulated sectors. I would offer two observations at this point.

First, the changes Ofgem is implementing make a lot of sense to this outside observer. There are very good reasons why the regulatory regime should provide equity investors with a return that indexes in line with out-turn inflation. There isn’t a justification - that I have heard - why equity returns should move 2-for-1 with inflation.

Second, it’s never particularly ideal if different regulators choose to build their regulatory frameworks on markedly different foundations. As I hope this post has highlighted, inflation indexation is one of the fundamentals in any framework of economic regulation. If Ofgem provides for one system of indexation, and Ofwat, the CAA, etc. have a different system, for no good reason, that’s not a great signal of regulatory consistency and predictability. It would be nice to think, therefore, that we are going to see some form of cross-sectoral regulatory alignment emerge in the next few years.

Notes:

* On the CPIH measure of inflation. A regulated firm that has been lucky enough to have RPI indexation over some or all of the last four years will have enjoyed an even greater inflation surprise.

** I am focusing in this post solely on the consequences of RAB indexation. I should record, for completeness, that certain regulated companies - e.g. in the water sector - have simultaneously under-performed against other elements of their price control allowances.

*** Ofgem’s RIIO-3 draft determinations, published last week, propose that there will be a single, common nominal/index-linked blend for all gas networks and a different common nominal/index-linked blend for the electricity transmission networks, reflecting the companies’ different projected uses of nominal and index-linked debt.